THE TWELVE BRONZE STATUES AND THEIR STORIES

The twelve women chosen to be depicted as bronze statues in the Virginia Women’s Monument represent women from all corners of the Commonwealth, both widely-celebrated women, as well as those with previously unknown, but equally important, stories. Many more women will be memorialized on the Wall of Honor and in the accompanying virtual educational modules.

Anne Burras Laydon

Colonist

b. ca. 1594 – d. after 1625

Jamestown

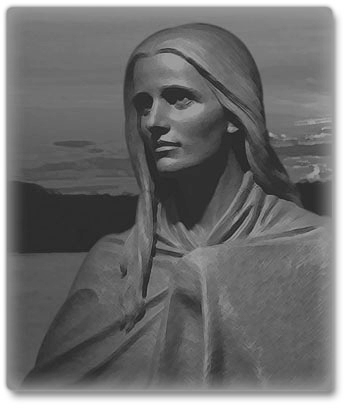

Cockacoeske

Pamunkey Chief

fl. 1656 - 1686

Middle Peninsula

Mary Draper Ingles

Frontierswoman

1732 - 1815

New River Valley

Anne Burras Laydon

Anne Burras Laydon represents the women who sailed to Virginia and survived deprivation to establish a thriving colony. She arrived in Jamestown in 1608 as a maidservant to “Mistress Forrest.” In December 1608, Anne Burras married carpenter John Laydon in what was recorded as the first English wedding to take place in Virginia. Early in their marriage, Anne Laydon was employed as a seamstress, and records indicate that during the strict military regime under Governor Thomas Dale, she was beaten because shirts she had sewn were deemed faulty. As a result of her punishment, she suffered a miscarriage. The Laydons survived the Starving Time and the hostilities of 1622, and by 1625, the couple and their four daughters were living in Elizabeth City County. Language in a land grant dated May 5, 1636, suggests that Anne Laydon may have still lived. There is no record of her death or burial.

Cockacoeske

Cockacoeske was a descendant of Opechancanough, brother of the paramount chief Powhatan. She became leader of the Pamunkey after the death of her husband in 1656. During the summer of 1676 Cockacoeske appeared before a committee of burgesses and Council members at Jamestown and after reminding them that her tribe had earlier lost a hundred men fighting alongside the colonists, she reluctantly agreed to provide a dozen warriors to help defend the colony against frontier tribes. Despite a March 1676 treaty between the Pamunkey and the colony, Nathaniel Bacon and some of his followers attacked them, capturing and killing some of Cockacoeske's people and forcing her to hide in Dragon Swamp. In February 1677 she asked the General Assembly for the release of the captives and the restoration of destroyed property. Cockacoeske was an astute leader and skillful politician. On May 29, 1677, when the Treaty of Middle Plantation was signed, at her request several tribes were reunited under her authority, and she signed the treaty on behalf of all the tribes under her subjection. Cockacoeske was unsuccessful in re-creating the chiefly dominance enjoyed by her people's leaders during the first half of the seventeenth century, but she continued to rule the Pamunkey until her death on an unrecorded date before July 1, 1686.

Mary Draper Ingles

The daughter of recent immigrants from Ireland, Mary Draper moved with her family from Philadelphia to the Virginia frontier. They settled at Draper's Meadow (later Blacksburg). About 1750 she married William Ingles. On July 30, 1755, Shawnee attacked the settlement, killing several people and taking Mary Ingles, her two sons, and her sister-in-law captive. They were taken to a Shawnee town near what is now Chillicothe, Ohio, where Ingles was forced to sew shirts for the men. During her captivity, her younger son died and her other son was sent to live in another town. In October after her capture, Ingles escaped with another female captive and traveled five or six hundred miles, much of it across rugged mountains and valleys. Making the last part of her trip alone and in a canoe that she discovered, Ingles encountered her husband at a frontier fort. Ingles had three daughters and another son. She and her husband moved to the banks of the New River near the site of what became the city of Radford, where in 1762 he received permission from the General Assembly to operate a ferry service. Following the publication in the nineteenth century of the story of her captivity and escape as she had told it to her youngest son, Mary Draper Ingles became one of the most famous Virginia frontierswomen.

Martha Washington

First Lady

June 2, 1731 – May 22, 1802

Fairfax County

Clementina Rind

Printer

ca. 1740 – September 25, 1774

Williamsburg

Elizabeth Keckly

Seamstress and Author

February 1818 – May 26, 1907

Dinwiddie County

Martha Washington

The daughter of a New Kent County planter family, Martha Dandridge received an education and at age eighteen married the wealthy Daniel Parke Custis. After his death in 1757, she inherited 17,500 acres of land and 300 slaves. Martha Custis married George Washington in 1759 and they moved to Mount Vernon, where she was responsible for managing the estate's domestic operations. Although they had no children of their own, they raised Martha Washington's two surviving children and later two of her grandchildren. An engaging companion, she joined her husband at his winter camps during the Revolutionary War. She was the general's closest confidant, and served as his secretary and as his representative at official functions. She comforted sick and wounded soldiers and her presence helped boost the camp's morale. When George Washington was elected president, Martha Washington understood that her behavior would set a precedent for the wives of the country's future chief executives. Among her important initiatives was establishing weekly receptions at the presidential mansion that were open to anyone, including members of Congress, visiting dignitaries, and local residents. She died at Mount Vernon on May 22, 1802.

Clementina Rind

Clementina Rind was the first woman printer in Virginia and exemplifies colonial Virginia businesswomen. Where she was born and when she married William Rind remains a mystery, although she may have been a native of the Netherlands who in 1756 arrived in Maryland, where her husband apprenticed. The couple settled in Williamsburg, Virginia, in 1765, and William Rind began publishing the Virginia Gazette on May 16, 1766. When he died in August 1773, Clementina Rind continued publishing the newspaper without missing an issue. She maintained the Virginia Gazette as a nonpartisan newspaper that, in addition to political news, contained a wide range of articles that indicated a special interest in science, philanthropy, and education. She appealed to her female readers by including poems and letters of advice. Rind petitioned the General Assembly to be appointed the colony's public printer, and in May 1774 she was elected by a two-to-one margin over two male printers. In 1774 her shop printed A Summary View of the Rights of British America, Thomas Jefferson's thoughts on the excesses of the British Parliament and King George III. The mother of five children, Clementina Rind died on September 25, 1774 and was buried probably next to her husband in Bruton Parish Church graveyard.

Elizabeth Keckly

Elizabeth Hobbs was born enslaved in Dinwiddie County and as a young woman suffered brutal beatings and sexual abuse that resulted in the birth of her son. Taken to Saint Louis by her owner's daughter, she married James Keckly, an enslaved man who had misrepresented himself as free. She began to earn money as a seamstress and with the help of her patrons she and her son were freed in 1855. They moved to Washington, D.C., where she developed a clientele that included many prominent women. Elizabeth Keckly came to the attention of Mary Todd Lincoln and in 1861 became her personal dressmaker and confidante. During the Civil War, Keckly helped establish the Contraband Relief Association to provide assistance for black refugees. After Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, Keckly resumed her dressmaking career in Washington. To help raise money for the indebted Mrs. Lincoln, Keckly wrote Behind the Scenes, Or, Thirty Years a Slave, and Four Years in the White House (1868; the publisher misspelled her name as Keckley, which subsequently became the most commonly used spelling). The book upset the Lincoln family and few copies were sold. Keckly continued sewing, and in the 1890s taught sewing and domestic arts at Wilberforce University, in Ohio. She died on May 26, 1907, at the National Home for Destitute Colored Women and Children, in Washington, D.C., which she had helped establish.

Sally L. Tompkins

Hospital Administrator

November 9, 1833 – July 25, 1916

Mathews County

Maggie L. Walker

Entrepreneur and Civil Rights Leader

July 15, 1864 – December 15, 1934

Richmond

Sarah G. Jones

Physician

February 1866 – May 11, 1905

Richmond

Sally L. Tompkins

Born in Mathews County into a wealthy family, Sally Louisa Tompkins moved to Richmond shortly before the beginning of the Civil War. On July 21, 1861, she and other women of Saint James Episcopal Church opened a private hospital in the home of Judge John Robertson to care for wounded soldiers. From the arrival of the first patient on August 3, 1861, until the departure of the last patient on June 13, 1865, Tompkins and her staff treated 1,333 patients, of whom only 73 died, the lowest mortality rate of any military hospital during the war. On September 9, 1861, Secretary of War L. P. Walker signed a letter appointing Tompkins a captain in the Confederate army in a possible ploy to enable Tompkins and the Robertson Hospital to receive supplies from the CSA Quartermaster Office. Tompkins accepted the appointment but refused to accept pay for her work. She was known as an efficient administrator whose insistence on cleanliness contributed to the high survival rate of the patients. After the war, Tompkins continued her involvement with charitable works and nursing. Her personal fortune depleted, she lived at the Home for Confederate Women in Richmond from 1905 until her death on July 25, 1916. Sally Louisa Tompkins was buried in the Christ Episcopal Church graveyard in Mathews County.

Maggie L. Walker

Born in Richmond on July 15, 1864, Maggie Lena Mitchell graduated from the Richmond Colored Normal School and became a teacher. On 14 September 1886, she married Armstead Walker Jr. The couple had three children, and by 1904 they were living in Richmond's Jackson Ward, a vibrant African American neighborhood. Maggie Walker joined the Independent Order of Saint Luke, an African American fraternal organization, in 1881 and rose through the ranks. She became Grand Secretary and steered the Order to fiscal security. In 1901 she declared her intention to expand the Order's services to its members to include a bank, a newspaper, and a department store. The Saint Luke Penny Savings Bank opened in November 1903 with Walker as its president, making her the first African American woman to establish and be president of a bank. A voice for civil rights, Walker helped to organize a 1904 protest against the Virginia Passenger and Power Company's policy of segregated seating on Richmond's streetcars. In 1921 she sought election as superintendent of public instruction on the "Lily Black" Republican ticket that featured John Mitchell Jr., editor of the Richmond Planet, as the gubernatorial candidate. Maggie Lena Walker died on December 15, 1934. Her home, a National Historic Site, is owned and operated by the National Park Service.

Sarah G. Jones

Sarah Garland Boyd grew up among Richmond's black elite and became a teacher after graduating from Richmond Colored Normal School in 1883. Five years later she married fellow teacher Miles B. Jones. Sarah G. Jones entered Howard University's medical school in 1890 and earned her medical degree in 1893. On April 27, 1893, she became the first African American woman to pass the Virginia Medical Examining Board's examination. Jones established a successful practice in Richmond and offered a one-hour free daily clinic for women and children. During the 1890s Jones was one of only three female physicians and about half a dozen African American physicians in the city. In 1902, she and her husband, who had also earned his medical degree, helped create the Medical and Chirurgical Society of Richmond for African American doctors. Jones and several of the society's members opened a hospital for black patients in 1903 and an associated training school for nurses soon thereafter. She became ill after caring for a patient and died on May 11, 1905. In 1922 the Sarah G. Jones Memorial Hospital, Medical College and Training School for Nurses (later Richmond Community Hospital) was named in her honor.

Laura S. Copenhaver

Entrepreneur and Lutheran Lay Leader

August 29, 1868 – December 18, 1940

Smyth County

Virginia E. Randolph

Educator

May 1870 – March 16, 1958

Henrico County

Adèle Clark

Suffragist and Artist

September 27, 1882 – June 4, 1983

Richmond

Laura S. Copenhaver

A confidante and mother-in-law of the writer Sherwood Anderson, Laura Lu Scherer Copenhaver continued a family tradition of service to the Lutheran Church. She wrote fiction, poetry, and dozens of church pageants, and one of her poems, "Heralds of Christ," became a well-known hymn. Her advocacy inspired the Women's Missionary Society of the United Lutheran Church in America to establish the Konnarock Training School to provide elementary-level academic and religious education for Smyth County children who did not have access to other public schools. As a director of information for the Virginia Farm Bureau Federation, in Marion, Copenhaver advanced strategies for developing southwestern Virginia's agricultural economy. She emphasized the importance of cooperative marketing of farm products in order to improve the standard of living for farm families. She practiced such cooperative strategies herself by coordinating the production of textiles out of her home, Rosemont. She hired women to produce coverlets based on traditional patterns and using local wool. Rosemont Industries expanded its offerings to include a wide variety of rugs, bed canopies and fringes, and other household items, some woven, knitted, or crocheted by hand and others manufactured by machine. Rosemont's popular textiles attracted customers from throughout the United States and from Asia, Europe, and South America. After her death on December 18, 1940, it was incorporated as Laura Copenhaver Industries.

Virginia E. Randolph

The child of former slaves, Virginia Estelle Randolph attended the Richmond Colored Normal School and taught school in Goochland, Hanover, and Henrico Counties. While teaching at Henrico's Mountain Road School she developed her unique approach to education by creating a successful formula based on practicality, creativity, and involvement from parents and the community. A firm believer in learning through doing, Randolph combined academic instruction with lessons on cooking, weaving, and gardening. Because of her innovative teaching style, in October 1908 she became the first Jeanes Supervisor Industrial Teacher, a position she held for more than forty years. As such, she received support from the Jeanes Fund, which was set up in 1907 by Philadelphia philanthropist Anna Jeanes to improve education for African American youth in rural schools. Randolph's work took her throughout the South and earned her a national and international reputation as a leader in education. In 1915 the Virginia Randolph County Training School was constructed as a high school for African Americans in Henrico. In recognition of her success, Randolph received a William E. Harmon Award in 1926. She died on March 16, 1958. In 1970 the Virginia Randolph School was dedicated as a museum, and in 1974 the Virginia Randolph Cottage became a National Historic Landmark.

Adèle Clark

An accomplished artist, Adèle Clark studied at the New York School of Fine and Applied Arts. She taught at the Art Club of Richmond and cofounded the Atelier, a training ground for a generation of Virginia artists. She applied her sharp intellect, artistic skills, and determination to champion women and the arts. Clark's interest in the woman suffrage movement began in 1909 when she helped establish the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia. She helped direct legislative initiatives, designed and drew postcards, organized suffrage rallies, and went on speaking tours to establish chapters throughout the state. After woman suffrage resolutions were defeated in the General Assembly, Virginia suffragists focused on passage of a federal amendment, although Virginia did not ratify the Nineteenth Amendment until 1952. Clark was selected as the first chair of the newly organized Virginia League of Women Voters in 1920 and served as president in 1921–1925 and 1929–1944. Her work involving social issues and governmental efficiency expanded in 1924 when she was elected to the board of the National League of Women Voters. During the 1930s, Clark was the Virginia Arts Project Director of the Work Projects Administration, providing employment opportunities for artists in the state. After converting to Catholicism in 1942, she helped organize the Richmond Diocesan Council of Catholic Women and shape its legislative program. She was instrumental in establishing Virginia's Art Commission, of which she was a member from 1941 to 1964. She died on June 4, 1983.